- Home

- Mary Losure

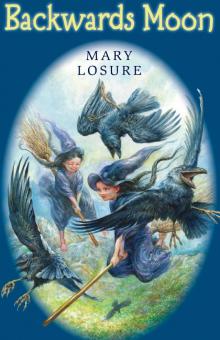

Backwards Moon

Backwards Moon Read online

Backwards

Moon

Mary Losure

Holiday House / New York

Text copyright © 2014 by Mary Losure

All Rights Reserved

HOLIDAY HOUSE is registered in the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office.

www.holidayhouse.com

ISBN 978-0-8234-3253-0 (ebook)w

ISBN 978-0-8234-3254-7 (ebook)r

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Losure, Mary.

Backwards moon / by Mary Losure. — First edition.

pages cm

Summary: When the magical veil that protects their valley from humans is broached and the Wellspring Water needed to repair it is polluted, it is up to two young witches, Bracken and Nettle, to save the coven.

ISBN 978-0-8234-3160-1 (hardcover : alk. paper)

[1. Witches—Fiction. 2. Magic—Fiction.] I. Title.

PZ7.L9Bac 2014

[Fic]—dc23

2013045643

For DCL, Witchfriend extraordinaire then, now, and always

chapter one

It was a good day for flying: pale blue sky, wispy clouds, gentle updrafts. It was also the last ordinary day before everything changed forever.

Nettle didn’t know that, but then, you never do.

Bracken, her cousin, wanted to visit the marmots. “We can just talk to them,” said Bracken. “What’s wrong with sitting and talking?”

“On a day like this?” said Nettle. “On a perfect day for the Raven Game?”

“Fine.” Bracken sighed as they glided over the Least and Middle Meadows. Soon they were flying toward slopes of bare, tumbled rock.

Like all witches, they had deep violet-blue eyes and black hair. They wore it in two long braids, which was the way you did before you turned fifteen. Nettle was small and quick and stubborn. Bracken, even though she was older and taller, tended not to argue with her.

They flew higher, toward dark fir forests. In the distance rose the jagged, snowy tips of the mountains that ringed the valley.

“You call the ravens,” said Nettle. “You’re better at it.”

Bracken gave a piercing whistle. A moment later, four ravens lifted out of the forest.

“Nice,” said Nettle softly. She and Bracken bowed their tall-pointed hats in greeting, then ravens and witches spiraled upward into the dome of the sky.

Nettle liked the Raven Game. There was a rhythm to it: dive, soar, dive. Nettle’s stomach always dropped thrillingly before she shot back upward. Sometimes as they dove they let themselves tumble over and over in the air. The ravens always laughed their throaty raven laughs, their claws extended in a most undignified fashion. They did it over and over again, until everyone but Nettle tired of it. Then the ravens looked at each other, gave a few parting caws, and flapped away.

“Did you ever notice how they never say anything?” said Bracken. “I wish at least sometimes we could talk to them.”

“You can’t talk to ravens,” said Nettle. “They won’t stay still long enough.”

“I wish there were some combination of ravens and marmots.”

Nettle raised her eyebrows. “Flying marmots? Tunneling ravens?”

“You know what I mean,” said Bracken soberly. “Someone who would talk to us and be fun to play with.”

“Yes. Well,” said Nettle, looking away. They hovered for a minute, their faces still, and Nettle knew they were both thinking the same thing: how all the other witches in the valley were long past any kind of game except the kind you play sitting around a table after supper. They were not just old, they were very old. Some were hundreds of years old.

It was late now. Shadows had spread across the rock slopes. Soon the mountains would be silhouetted against the glowing sky, their snowy tips tinged with pink. “Maybe tomorrow we can play Catapult,” said Nettle. “Catapult works fine with just two.”

Bracken nodded and pulled her black hat low on her forehead. Not to stop it falling off, because it wouldn’t, being magic. It was just something she did when she was thinking about The Way Things Were. Nettle pulled hers down too. Then with one motion, they wheeled their broomsticks toward home.

chapter two

Nettle and Bracken followed a stream, silver in the fading light. It flowed through thickets of willow bushes, then dropped to the clear pools where the two of them often swam. Lower still, the stream widened to a river that wound in broad bends across the valley floor. When they came to Five Herons Marsh, they turned due east. Then they slowed their brooms and skimmed above the forest.

It was dark now, but with their Nightseeing, Nettle and Bracken could make out an open spot just ahead. They glided low over pumpkin vines and rows of corn. In the daylight, the cornstalks would be tawny and the pumpkins golden, but now they looked gray, yet clear in every detail, the way things did with Nightseeing.

In another moment Nettle could make out stone roofs, cone-shaped like witches’ hats, here and there among the oak branches. Crooked chimneys and many-paned gable windows glinted palely in the starlight.

Nettle and Bracken landed on the small, circular clearing that was the village Commons and swung off their broomsticks. The scent of wood smoke lingered pleasantly in the air. From a front porch a distant banjo twanged, clear and merry, mixing with the faint murmur of old voices and high, cracked laughter.

Nettle and Bracken ran lightly across the Commons and up their own front steps. No light shone inside, which meant that their Great-Aunt Iris was out on somebody else’s porch. Their aunt, who loved them dearly but tended to forget things, would be home when she thought of it.

Nettle and Bracken pushed open the door. A pot of lentil stew, now cold, sat on the back of the stove. Still, Nettle liked lentils, and it wouldn’t take long to warm them up. She piled wood and kindling, lit them with a spark from her finger, and shut the stove door with a clang.

Bracken put on the kettle for meadow-mint tea and lit the lantern that hung above the table. It made a warm, golden light—much cheerier than gray Nightseeing.

Nettle ate her supper quickly, thinking about which aspen grove they should go to the next day and how to choose the right sapling, with just the right springiness. She imagined the biggest rock they could fling and the clatter and boom it would make as it bounced crazily down the slopes. . . . Catapult was a fine, fine game.

They washed the dishes—it was too bad that magic wouldn’t stoop to bothersome everyday tasks—and set them back in the cupboard. Nettle went out on the porch to toss the dishwater out, whoosh, and stood for a moment. Above her untold numbers of stars glittered among the oaks’ crooked branches. The Cat’s Highway arched through them, a starry path that seemed to come from, and go to, the world on the other side of the mountains. As she often did, Nettle imagined herself flying along it. Then she went inside, her bare feet padding softly on the wooden floor, and climbed the ladder to the sleeping loft she shared with her cousin.

Bracken was already in bed, reading the Cyclopedia of World History by the light of a single candle. It was the only human-made book in the entire village. Bracken had read it over and over.

Nettle had read it too, though only once. She’d studied all the pictures.

“Where are you now?” Nettle asked as she hung her hat on the bedpost.

“The part where they invent the steam locomotive and the telegraph,” said Bracken. So she was nearly at the end.

Nettle stepped out of her dress and left it lying on the floor.

“You’re not going to brush your hair?” said Bracken without looking up.

“No,” said Nettle, and slipped into bed. She waited while Bracken read the last few pages of the book, which were all about Onward and Upward and the bright future of Mankind from

this glorious day forward.

Bracken closed the book and stared into the distance, picking absently at the blanket on her lap. Nettle could tell from her troubled look that Bracken was thinking about their parents and where they had gone.

Nettle’s and Bracken’s fathers—like all witches’ fathers—were Woodfolk. When a Woodfolk man and a witch got married, their children were always tiny witches, with dark violet-blue eyes and spikey black hair. But long ago, when Nettle and Bracken were only babies, their fathers had vanished, along with the entire Woodfolk tribe. Their mothers had gone looking for them, and then they too had vanished.

And ever since, no one would ever talk about it.

“I don’t think humans had anything to do with why our parents are gone,” said Nettle now.

Bracken didn’t say anything.

“Humans have no magic,” said Nettle.

Bracken shrugged.

“Bracken, they can’t even see us.”

“Human children can,” said Bracken.

“They can’t be all that dangerous,” said Nettle. “And what about Witchfriends?” (Witchfriends were special humans who, even when they were grown up, could see witches.) “There’s no need to be afraid of them, obviously.”

“Then why do we live so far away from the human world?” asked Bracken, as she had a hundred times before. “If humans are harmless, why would Rose and Scabiosa and the rest go to all the trouble of spell-spinning a Veil across the pass to keep them out?”

“I think it’s to keep us in,” said Nettle. Because it was true: whenever they flew too close to the pass that led to the outside world, their broomsticks turned around of their own accord.

“But why?” asked Bracken.

It was no use asking. Rose (who was sort of the leader of the village but not really, since witches didn’t believe in having leaders) would only gaze at you with her deep, old eyes and say there was no telling what the humans were up to these days and she for one didn’t want to find out. Somebody else would change the subject, and that would be that.

It was obvious that the older witches had decided not to answer certain questions. Perhaps they’d done it late at night, all sitting around the Gathering Fire, in accordance with the ancient tradition of witch decision-making. Though in practice this always led to a lot of time-consuming arguing. . . .

So maybe it was just something Rose or Scabiosa had decided and the rest went along with, as often happened. But in any case, it came out to the same thing: it was no use asking.

“I think we should ask the wolves,” said Bracken. “They’ve been through the pass lots of times. They must know about humans.”

“Yes,” said Nettle, sitting up.

And at that very moment, a wolf howled.

Far away in the night, a second wolf answered. A chorus of yips and barks rose, then faded away.

“See?” said Bracken. “It’s an omen.”

And maybe it was, though not the way they thought.

chapter three

Neither Nettle nor Bracken had ever actually talked to a wolf, and even spotting one was never easy. Bracken thought they would be easiest to find in the meadows, but she and Nettle had flown all day and not seen one. Wolves were clever that way.

Nettle thought they’d be on the bare rock slopes below the peaks, but Bracken said they weren’t there, obviously. Did she see any?

“What would be so wrong with just flying up closer?” said Nettle.

“It’s late,” said Bracken, in that annoying I Am Older voice she sometimes used. “We have to get home.”

“We do not,” said Nettle. “Aunt Iris won’t even remember we’re gone. And besides, we wasted all day looking where they weren’t. Now let’s go where I wanted to go.”

“Oh, all right,” said Bracken. So they flew higher.

“See?” said Bracken finally. “Now let’s go home.” She turned around and skimmed toward the village.

Nettle took one last look at the slopes. Then she stopped, hovering.

“Bracken, wait!” she called.

Bracken made a graceful swoop around.

“Look there!” said Nettle, pointing. Two tiny, distant shapes were making their way, very slowly, down the slope.

“Those aren’t wolves,” said Bracken, staring. “They’re walking on two legs. And they’re wearing trousers!”

Nettle caught her breath. “Bracken! Do you think they might be . . . ?” She glanced at her cousin, hardly daring to hope.

Bracken shook her head. “They’re not Woodfolk. They can’t be! Look at the way they move, so slow and heavy. Nobody magic would move like that.”

“Oh,” said Nettle dully. She felt sick with disappointment.

“I would know Woodfolk if I saw them,” said Bracken quietly. “I would know them instantly.”

Nettle squeezed her eyes tightly shut and rubbed them with her sleeve. Then she stared, again, at the slope.

The tiny figures plodded steadily lower, picking their way around boulders and edging across falls of broken, loose stone. A rock dislodged by their feet clattered down the mountainside, the sound echoing across the vast landscape.

“Nettle, those are humans!” said Bracken. “They can only be humans.”

Nettle turned to stare at her. “But . . . how could one get in?”

“Something must have gone wrong with the Veil.”

“But how . . . ?”

“I don’t know,” said Bracken fiercely. They hovered, staring. “Maybe we should go back and tell the others.”

“I want to see one,” said Nettle. “They can’t see us. What’s the harm? Come on,” she said, and flew toward them.

“Nettle,” said Bracken, but she followed.

A shrill cry sounded above them. Kree! Kree! Kree! A hawk circled high in the sky, peering down at the humans.

They were men, both of them. They had big, heavy-looking bundles on their backs and wore odd little caps with brims like ducks’ bills. And their feet were not bare, like witches’ feet. Their toes were trapped in . . . in . . . what? Boots, Nettle thought they were called.

Nettle leaned down. “Humans?” she called.

The walkers stopped. Their eyes—which were a strange pale blue, not the deep violet-blue of witches’ eyes—looked toward the sound, unseeing.

“Did you hear that?” cried one. His hair was the color of sand.

The two humans peered upward nearsightedly, like moles.

“Yes,” said the other, bigger one.

“Did it sound like . . . a voice?’ ” asked the sandy-haired one. “Sort of a high voice. A girl’s voice.”

“They can’t see us!” whispered Nettle. “They really can’t!” It was amazing, being invisible. She liked it.

“Listen!” said Sandyhair, stopping. “It’s like . . . like ghosts,” he muttered.

“That’s ridiculous,” said Big One, but now they walked faster, glancing all around.

“Humans?” said Nettle again, but this time she had switched to the Language: the silent way of talking, like thoughts traveling, that you used when you talked with animals. “Oh, humans?” she called again in the Language, but they only hurried forward.

“Hello?” said Nettle in the Language.

Her skin prickled. It was odd, not being seen or heard.

“Check the GPS again,” said the first human suddenly.

Big One pulled out a little flat box.

“What’s that thing he’s holding?” said Nettle in the Language. She hovered nearer, trying to see.

“It must be one of their inventions!” replied Bracken in the Language.

With his thumb, Big One jabbed at the box. “This makes no sense,” he said. “It’s like this valley isn’t even on the map. There’s still only this blank, blurry space.”

“Really?” said Sandyhair. “Could it be out of satellite range?”

“I don’t see how.” Big One jabbed the box again, then stuck it in his pocket before Nettle had tim

e to see.

“Drat,” she muttered.

“There’s something creepy about this valley,” said Sandyhair. “I think we should turn back.”

“But . . . it’s so beautiful,” said Big One softly. He gazed out over the vast sweep of forest and meadow, to distant waterfalls that hung like white threads against the cliffs.

“I’ve hiked all over the world,” he said slowly. “And I’ve never seen wilderness like this. Never.”

The hawk’s high, shrill call sounded again. It swooped lower, hovered near Nettle and Bracken, and glared at them with its fierce yellow-ringed eyes. “What’s wrong with you two? What are you waiting for? Get rid of them!”

“Get rid of them?” said Nettle, gaping.

The hawk nodded grimly.

chapter four

“You mean kill them?” gasped Nettle.

“Witches don’t just . . . kill things,” said Bracken slowly.

“Stun them, then,” snapped the hawk. “Get them out of here.” He jerked his sharp, curved beak at the humans. “Use those finger sparks of yours.” He soared higher and circled around, his wings beating the air.

Nettle and Bracken stared at each other.

“I stunned a rabbit I was mad at, once,” said Nettle slowly.

“You did?” said Bracken, startled.

“He was fine. Well, later he was.”

Bracken furrowed her forehead.

“I’ll do it,” said Nettle. She swooped down, aimed her index finger at Sandyhair, and shot out a long silver spark. He fell to a sitting position, toppled sidewise, and slid to a stop on the sloping ground.

Big One stared down at him, goggle-eyed.

Nettle shot another spark. Big One sank, slid, and came to rest with his bundle underneath him. He looked like a turtle turned upside down.

“Are they breathing?” gasped Bracken, landing.

“They’re . . . fine,” said Nettle nervously. And they really did seem to be.

The hawk dived down, his sharp talons reaching toward the limp and helpless humans. Then he veered away. Next to the humans’ bulk, he looked like a delicate bundle of feathers and bones, Nettle noticed with a shock. His eyes were like dark glass.

Backwards Moon

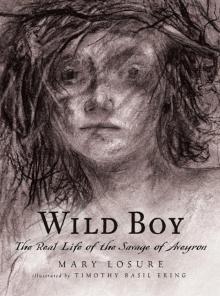

Backwards Moon Wild Boy

Wild Boy