- Home

- Mary Losure

Wild Boy Page 2

Wild Boy Read online

Page 2

Bonnaterre, who taught natural history at a school for boys, was very, very interested.

Like other naturalists, Bonnaterre examined plants and animals, compared them with others, and fit them into categories. Birds were creatures to be captured and preserved, stuffed, with tufts of cotton where their eyes had been and labels hung from their tiny claws. Butterflies were specimens to be taken by their bright wings and stuck through with pins. A portrait of Bonnaterre shows him sitting very upright at his desk, wearing a tight collar and a cold, slightly pained expression. A collection of specimens lies at his elbow: a shell, a snake, and a small, wide-eyed fish that, if not yet dead, soon would be.

Now the professor hoped to have something new to study.

Why should scientists in Paris get the first chance? Bonnaterre was closer, and quicker. He went to see a government official and asked to have the wild boy sent to Rodez’s Central School, where Bonnaterre was a teacher.

And so it was that the next part of the wild boy’s life began.

The wild boy had been in the orphanage for three weeks when, on a February morning of the year 1800, a carriage and driver pulled up to the stone gates. When it drove away again, the boy was inside.

All that day and the next, the carriage jolted through winter-bare fields and forests until at last it came to a great hill. At its crest stood two pale, square towers, tall against the sky: the great cathedral of Rodez.

The carriage labored up the hill, past the fortress-like stone walls that surrounded the city. Soon, it rolled into the public square at the foot of the cathedral. From the cathedral’s heights, gargoyles grinned down.

The carriage clattered along twisted, narrow streets till it stopped at the carved stone entranceway of the Rodez Central School.

As the wild boy stepped down from the carriage, gawkers swarmed all around.

Eyes stared at him as they had, long ago now, in the village square in Lacaune. Faces jabbered. Bodies crowded in tight, shoving and jostling. . . .

And when they came too close, the wild boy bit them.

“It was only with some difficulty that he was led within the confines of the Central School,” an official wrote. The school’s huge wooden doors creaked open. Strangers hurried the wild boy through.

Then the doors swung shut behind him.

What is it like to be treated not as a person, but as a specimen?

The wild boy would soon find out.

Professor Bonnaterre examined the wild boy’s body, taking careful measurements.

“When he raises his head, there will be seen . . . a horizontal scar of some 41 millimeters in length, which seems to be the scar of a wound made with a cutting instrument,” Bonnaterre wrote.

The professor counted the burns on the wild boy’s face. “There is one on the right eyebrow; another in the middle of the cheek on the same side; another on the chin; and another on the left cheek,” he wrote. Bonnaterre noted down the six long slashes that ran the whole length of the boy’s arm. “His whole body is covered with scars,” Bonnaterre wrote.

He didn’t bother to write down the expression on the boy’s face as he was poked and prodded and measured.

The professor did wonder whether the scar on the wild boy’s throat was evidence that someone had tried to kill him and left him for dead in the forest. “Did some barbaric hand, having led the child into the wilds, strike him with a death-dealing blade?” he asked. But nowhere, in all the long report he was later to write, would he show a glimmer of sympathy or a shred of affection for the motherless, fatherless boy who was now in his care.

Bonnaterre gave the boy a label — the Savage of Aveyron — and made careful observations on how the Savage’s habits and manner compared with those of other wild children found in historical records: a boy found living with wolves in Germany in 1544; a boy discovered among bears in Lithuania in 1661; a boy in Ireland who lived with a flock of sheep, year not given; and five wild boys and three wild girls found in various places in Europe throughout the 1700s.

Some scientists actually believed that such wild children belonged to a different species, Homo ferus, or Wild Man.

If they did belong to a whole different species, and the wild boy was one of them . . . was he even a human being?

Bonnaterre stared at him, trying to decide.

The professor made the wild boy take a series of tests.

In one, Bonnaterre held a mirror in front of the boy’s face.

At first, to try to find the person he saw in the mirror, the wild boy looked behind it. When that didn’t work, he brought his gaze back to the mirror. Beside his own reflection, the boy saw someone holding a potato. The wild boy reached toward the mirror, but he couldn’t get the potato that way. Then, without turning his head, he reached behind him and grabbed it.

It was clever of the wild boy to get the potato by recognizing, almost instantly, how a mirror works.

Still, Bonnaterre decided that didn’t matter much.

In another test, he had music played — violins, perhaps, viola and cello and maybe a flute or two — and watched what happened next.

“The sounds of the most harmonious instruments . . . make no impression on his ear, or at least he appears to be insensitive to them,” Bonnaterre wrote, “and he shows no perception of the noises made next to him; but if a cupboard that contains his favorite foods is opened, if walnuts, to which he is very partial, are cracked behind him . . . he will turn around to seize them.”

Not being interested in music, but paying attention to the creak of a cupboard door or the crack of a walnut — Bonnaterre considered that a black mark against the wild boy.

And there was worse to come.

“He has been seen, when tired, to walk on all fours,” Bonnaterre wrote.

It was, to Bonnaterre, a very important point. God and Man (“Man” was what scientists in those days called all human beings) walked upright, of course.

Only dumb beasts walked on all fours.

When he wasn’t being poked and prodded and tested, the wild boy could wander where he wanted inside the Central School.

It was an ancient stone building built around a courtyard and walled garden. Above each classroom entrance, the name of a subject was carved in stone. “Rhetoric,” said one. “Humanities,” said the writing above another doorway, but no one expected the wild boy to walk through it. A classroom, after all, was no place for a child like a wild beast.

What the school’s students thought of the wild boy or how he acted when he saw them was something no one will ever know, for it was never written down. Alone, in his bare feet and a rough tunic and leather belt that he was not allowed to take off, the wild boy padded down the long, cold corridors.

Spiral staircases led up to the school’s second and third stories. Some of the windows overlooked the central garden. Others had a view of the city streets. At one end of the school stood a round tower. If he climbed it, the boy could gaze out over the rooftops to open fields and woodlands.

Then one day, someone left the door to the outside world open . . . and the wild boy was out and running.

The streets were like dark stone tunnels with only a crack of light from above. But if the wild boy could reach the fields and woods, the sky would open wide! The gray city and the Central School would be left behind forever!

But in his odd costume and bare feet in the dead of winter, he was instantly recognizable as the Savage of Aveyron. He was spotted, caught, and brought back.

“He is always looking to escape and takes advantage of every occasion on which he finds the door open to get away,” Bonnaterre wrote. “He has already escaped four or five times from Rodez; but happily he was always retaken, sometimes at considerable distance from the town.”

The wild boy broke every window in his room, but they replaced them with linen too tough to tear. Once, he jumped from a second-story window. But whatever he did, it was no use; he was always caught.

He was angry sometimes, Bonnat

erre noted coldly. If someone made him mad, he’d make cries of rage or even give the person a sudden, well-aimed bite. Sometimes he’d place his closed fists over his eyes and hit himself, hard, in the head.

He took to spending hours alone in his room. “When it is time to go to bed, nothing can stop him,” Bonnaterre wrote. “He takes a torch; he points to the key to his room, and he becomes furious if not obeyed.”

“His sleep is very light,” Bonnaterre noted, “and he wakes at the slightest knock on the door. When the wind of the Midi [the mountain wind] blows, his bursts of laughter can be heard during the night and, from time to time, other vocal sounds that express neither pain nor pleasure.”

Most mornings, the wild boy woke at dawn. He would wrap himself in his blanket, head and all, and begin rocking. Back and forth he rocked, hour after hour.

Sometimes his face contorted as though he were having a seizure. Deep in his throat, the boy made a humming sound, a kind of dull murmur.

SNOW DRIFTED DOWN, past the leering gargoyles and frosted windows of the city. Inside the Central School, the only warm place was by the fire.

The wild boy was drawn to fires. They made him roar with laughter and shake his hands in signs of joy. The boy would lift his tunic as high as his leather belt so he could feel the warmth on his bare skin. If someone yelled, “For shame!” he’d drop it, Bonnaterre wrote. But a minute later, he’d lift it again.

Bonnaterre had heard the stories of how the wild boy had wandered naked and barefoot through the woods in the dead of winter, but now, watching the boy toast his bare bottom at the fire, he began to doubt them. “I could not imagine how an individual who had tolerated such severe cold could also be so sensitive to impressions of heat,” he wrote. Could it really be true that the wild boy didn’t feel the cold?

So Bonnaterre devised an experiment to find out.

“One evening, with the thermometer at four degrees below zero [25 degrees Fahrenheit] I undressed him completely and he appeared glad indeed to be rid of these garments,” Bonnaterre wrote. “Next I pretended to take him out into the open air; I took him by the hand through the long corridors, up to the main door of the school building.”

It was the same door through which the wild boy had tried to escape so many times before.

Now the sour, unsmiling man who was always staring at him had, for some reason, freed him from his hated tunic and the leather belt that held it tight. Now the man who never let him go was leading him outside!

“Instead of showing any reluctance to follow me, he dragged me out of doors by repeated yanks,” Bonnaterre wrote.

The dark, empty streets lay before them, and beyond that, the open fields. The forest!

Freedom.

And yet . . . the man would not let him free.

Another night, Bonnaterre crept silently into the wild boy’s room. The boy was asleep on his bed of straw, wrapped only in a linen sheet.

He lay curled up in a ball, with his fists jammed into his eyes and his face against his knees.

It must have been a sad sight, the wild boy curled up so tight against the world, but the scientist didn’t seem to feel any sympathy.

Instead, he ran his hands over the boy’s arms and legs to see if they were cold to the touch.

They weren’t, though. They were “comfortably warm.”

So it was true!

Two separate experiments had proved it to Bonnaterre’s satisfaction: the wild boy didn’t feel the cold. “He can be indifferent to the impressions of cold and [still] find pleasure in the gentle effects of heat, since we see dogs and cats with the same habits,” Bonnaterre wrote.

But what was it like for the wild boy, Bonnaterre’s latest experiment?

The boy’s burns and cuts and the slash across his neck had come from somewhere, even if he tried hard to forget them. And surely, the pain he’d suffered had left traces deep inside him.

Maybe, sometimes, he dreamed about a burning stick, jabbing at him. A knife blade, flashing.

And that night, when he felt Bonnaterre’s hand creeping over his body, did the boy wake to see a black shape looming over him in the dark?

Was he filled with terror?

Did it give him nightmares later?

It was no concern of Bonnaterre’s. After all, to him, the boy was only a specimen.

But there was one person who didn’t test the wild boy, or stare at him, or do experiments on him.

His name was Clair Saussol. He was the gardener at the Central School, but he’d also been chosen to be the wild boy’s caretaker. He was sixty-four years old and had come to Rodez from a tiny village in the countryside.

Clair Saussol was what educated people often referred to as a “simple peasant.” It’s likely he couldn’t read or write more than his own name. Because he was “only” a peasant, not much was ever written down about him.

But after a while, the boy began to follow Clair around like a puppy.

When spring came, Clair had soil to dig and seeds to plant, so most likely the wild boy would have gone with him to the garden. The boy’s lively dark eyes would have watched Clair as he turned the earth, releasing its rich spring scent. The boy would have watched as Clair’s workingman’s hands, as lined with dirt as his own, dropped in the seeds.

Beans, perhaps, or the flat, pale seeds of cucumbers.

The wild boy sometimes buried food to dig up later. Now, here in the garden, Clair was doing something very similar!

When the old man took up his spade and shuffled to another part of the garden, maybe the wild boy trotted after him to see what he’d do next.

Meeting Clair was one good thing at the Central School.Another was discovering different kinds of food.

“He was constantly occupied during his stay at Rodez in shelling green beans; and he fulfilled this task with an expertise appropriate to the most practiced man,” Bonnaterre noticed.

On his left, the wild boy piled the dried bean plants, with their pods, and on his right he put a pot to cook them in. “He opened the pods one after the other with an inimitable suppleness of movement,” Bonnaterre wrote. “As he emptied the pods, he piled them up next to him symmetrically: and when his work was through, he took away the pot, added water, and put it next to the fire which he fueled with the pods he had piled up. If the fire was out, he took the shovel and placed it in the hands of Clair, signaling him to go looking for some nearby coals.”

The wild boy discovered that potatoes didn’t always have to be roasted in a fire: he also liked them cooked in other ways. “When he felt like eating hash-browned potatoes, he chose the largest, brought them to the first person he found in the kitchen, tendered a knife to cut them into slices, went to find a frying pan, and pointed out the cupboard where the cooking oil was stored.”

After a while, when the wild boy went to the kitchen, he lifted every pot lid to see what was underneath it.

Instead of sniffing meat and rejecting it the way he had before, he tasted some — and discovered that he liked both meat and meat broth. When he found a pot of broth, he waited until the cook’s back was turned to dip in a piece of bread. Then he’d pop it in his mouth. “I saw him do [it] one day five or six times in a row without being caught,” Bonnaterre wrote.

One day the wild boy got a taste of sausage, and instantly it became one of his favorite foods.

The next day, wrote Bonnaterre, “a captain of the auxiliary battalion of Aveyron, who was dining in the room where the child was, signaled him to approach, by showing him a little piece of sausage he had cut from a larger piece on his plate; the young man approached to accept the offer. . . . With his left hand he took the morsel that the captain held between his fingers; with the other hand, he adroitly seized the rest of the sausage on the plate.”

As the boy scampered away with his prize, maybe the captain thought it was funny, but Bonnaterre didn’t seem to.

He recorded the incident solemnly, one more observation along with all the others he was colle

cting about this strange creature, this possible Homo ferus.

Bonnaterre had noticed that the wild boy followed Clair from place to place, but he didn’t think that meant the boy actually liked Clair. “His affections are as limited as his knowledge,” Bonnaterre decided. “If he shows some preference for his caretaker,” he wrote, “it is an expression of need and not the sentiment of gratitude; he follows the man because the latter is concerned with satisfying his needs.”

Bonnaterre didn’t think the wild boy was very bright, either. In fact, Bonnaterre suspected he was the kind of person that scientists in those days called an “imbecile.”

“Suspicion of imbecility,” Bonnaterre wrote in his report, and he tallied up what he’d observed, the results of the many tests the wild boy never knew he was taking.

“This child is not totally without intelligence . . . ; however, we are obliged to say that . . . we find only purely animal function: if he has sensations, they do not give rise to ideas. . . . He reflects on nothing.”

The boy had “no imagination, no memory,” the professor wrote. “This state of imbecility is reflected in his gaze, for he does not fix his attention on any object; . . . in his gait, for he always walks at a trot or a gallop; in his actions, for they lack purpose and determination.”

Whether it was true or false, fair or unfair, Bonnaterre’s verdict would soon be written down for all the world to see: the wild boy was, mostly likely, an imbecile.

By mid-July, the gardens in the courtyard of the Central School basked in the warm sun. Beans hung on the vines for the picking, but the wild boy would not be there to shell them. For an official order had come from Paris.

A group of Paris scientists calling themselves the Society of Observers of Man wanted their chance to study the wild boy. One of them had gone to see the French Minister of the Interior, a man named Lucien Bonaparte. Lucien Bonaparte was the brother of the mighty Napoléon Bonaparte, the ruler (soon to be emperor) of France.

The Minister had written a letter demanding to have the “unfortunate boy” sent to Paris. “I claim him,” Lucien Bonaparte had written to officials at Rodez, “and request that you send him to me forthwith.”

Backwards Moon

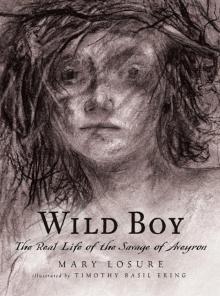

Backwards Moon Wild Boy

Wild Boy