- Home

- Mary Losure

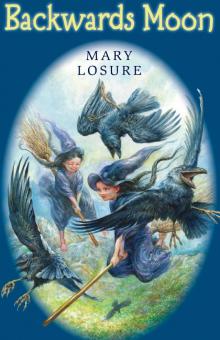

Backwards Moon Page 3

Backwards Moon Read online

Page 3

chapter six

Nettle woke to the pleasant smells of meadow-mint tea and wood smoke. Outside the sleeping loft window, the sun was high over Gaia’s Summit. For a moment Nettle couldn’t think why she would still be abed at this hour. Then she remembered everything.

She looked over at Bracken’s bed. It was empty. Nettle stood and slipped on her dress. She snatched her hat from the bedpost and crammed it on her head. Then she climbed swiftly down the ladder. Through the front window, she could see Bracken outside, huddled on the porch swing. Great-Aunt Iris lay fast asleep in her bed by the stove, her thin gray braid trailing on the floor. Nettle snuck past her, slipped through the door, and sat down beside Bracken on the swing. “It’s like the whole world has changed. In one day. Because of two humans.”

Bracken nodded. “What is it about them, that thing that makes them so dangerous that nobody will tell us?”

“Sedge said we should be told. We could ask her.”

“She can’t,” said Bracken. “They’ve all agreed.”

Part of being in a coven meant that when you agreed to something, you stuck to it. But Nettle and Bracken had both noticed that when it came to agreeing on things, some people’s opinions seemed to count more than others’, and that witchlings didn’t get a say at all.

“Bother,” muttered Nettle.

“Toadflax wanted to tell us,” said Bracken.

“We could try asking her,” said Nettle.

“But how could we find her? It’s no use going to her cottage.”

“True,” said Nettle soberly.

Toadflax’s cottage was built on a ledge halfway up the cliffs, and whenever you flew near it, the cottage disappeared. Whether you could even see it from the valley floor depended on the time of day: where the sun was, and the light and shadows on the cliff face.

Once, long ago, Nettle had flown up and stared for a long time at the spot where the cottage was supposed to be. But there was something about the shadows, the chill air . . . Nettle hadn’t wanted to land. She thought of that now, as the swing hung still. She didn’t feel like swinging.

In the silence, a hermit thrush sang. The notes cascaded down in perfect harmony, a waterfall of sound. Great Aunt Iris’s snoring stopped. A gentle bumping, then their aunt padded onto the porch and peered out over the railing. Sunlight filtered through tree leaves and made patches of gold on the forest floor.

“My, what a pretty day,” she said. “Are you off to the meadow again? Take some muffins. I made them yesterday, those ones with currants. The kind you both like.” Then she turned and frowned, as though she were trying to remember something. “That business with the humans. Did we get it cleared up?”

“Not exactly. Not yet,” said Bracken.

Great-Aunt Iris sat down in her rocking chair. “The Veil,” she said, rocking back and forth. “It seemed to me they said there was something wrong with it. That can’t be right, though. Can it?”

“They’re fixing it tonight,” said Bracken. “At midnight.”

“Good,” said Great-Aunt Iris. She leaned back and pushed with her strong, bare toes. The familiar clunk, clunk, clunk of her rocker mixed with the usual birdsong, as though this were any ordinary day.

Nettle wanted to go through the pass again, that morning.

“Please,” she begged. “It will only be open for today. Just until they fix the Veil. Come on, Bracken. Please.”

“I thought you wanted to play Catapult,” said Bracken.

“I did, but that was before.”

But for once Bracken wouldn’t budge. “I think we should stay in the valley. And don’t sulk, or I won’t play at all.”

So Catapult it was.

Nettle fetched some muffins and nuts and cheese and two bottles of blackberry juice and slipped them into her pocket. She had always taken her pocket for granted, but that morning it struck her how awful it would be if it didn’t work—if you had to put everything you wanted to carry into a bundle and lug it around on your back. If your only pocket was a pathetic little thing like the ones humans had . . .

It was then that she remembered the black box.

“The box!” she said. “We forgot about the box!” She pulled it from her pocket and jabbed it. It made its tiny unpleasant whine, but in the daylight its strange glow did not look so sinister.

“Remember how they said it was a map?” said Bracken suddenly. “The two humans, remember? They said it was a map.”

“We could use it to explore!” said Nettle.

“Maybe,” said Bracken, looking at it doubtfully.

“Let’s take it out to the sitting rock,” said Nettle. “Come on.” She hurried down the porch steps.

The sitting rock was a little way into the forest in a sunny clearing where leathery ferns grew. Nettle sat down and jabbed the box again. It seemed to be growing a bit weary. . . . It took longer for the whine to start and the light to appear. Nettle jabbed it again.

“Don’t just keep jabbing,” said Bracken. “Think first. There must be some sort of trick to it. . . . Here, let me have it.”

Nettle handed it to her.

They jabbed and stared, jabbed and stared. The light went on and off.

“This is making me dizzy,” said Nettle. She sighed and looked up from the box. Then she jumped, startled.

A creature peered out of the ferns, its pointed nose quivering. The air wavered, and Toadflax stood before them. “It’s no use looking at their maps,” she said. “Your way is a witch’s way.” Toadflax muttered something under her breath. The box sailed through the air and landed at her feet. Before Nettle or Bracken could move, it began to quiver. A series of small fires erupted from its glassy surface. A cloud of foul, acrid smoke drifted and twisted in the sunlit clearing.

Toadflax grinned sourly. “That takes care of that.”

“You might have asked!” said Nettle hotly.

Toadflax shrugged.

“What do you mean our way ‘is a witch’s way’?” said Bracken.

“You’ll find out soon enough,” said Toadflax. “At the Veilspinning.”

“What are you talking about?” snapped Bracken.

“ ‘Rose, you shouldn’t worry so,’ ” Toadflax mimicked in Scabiosa’s deep voice. “ ‘The Veilspinning will work, surely.’ ”

“How did you know she said that?” demanded Nettle. “You were listening in after you left!”

“Of course,” said Toadflax.

“You were that marten I saw.”

“True,” said Toadflax. “And don’t you wish you could do a spell like that?”

And with that, the air wavered. A scrabbling, the swish of a long tail, and she was gone.

chapter seven

“She wrecked the box without even asking!” said Nettle. “And I hate the way she sneaks around like that, listening and spying.”

Bracken nodded. “The others never change form like that. She has way more magic than they do.”

“What did she mean, our way is a witch’s way?”

Bracken raised her shoulders. “She said we’d find out. Then she made fun of Scabiosa for saying the Veilspinning will work.”

“Do you think the others will even let us come to the Veilspinning?”

“Probably not,” said Bracken.

“They can’t keep treating us like little bitty witchlings our whole life. They can’t,” said Nettle.

But it turned out they could: a Veilspinning was no place for witchlings, Rose said. Which meant they had to stay home.

It was almost midnight, and out their sleeping loft window, Nettle and Bracken could see dim gray shapes standing in a circle around where the Gathering fire would be if anyone had lit it.

Nettle counted off each pointed hat. “Six,” she said. “Seven, eight, nine. That means Toadflax is there. Do you think she’s even helping?”

“You would think so,” said Bracken. “If only to keep the humans out for her own selfish self.”

They watched as eac

h witch took a lantern from her pocket and lit it with a spark from her finger. The lights rose into the sky and hovered. Nettle could hear shrill voices as the group formed a wavering V. Like wild geese on the wing, they streamed toward the pass.

“Now?” asked Nettle, getting out her broomstick. Bracken nodded. They climbed to the window ledge, leaped onto their brooms, and sped after the lanterns.

“Keep back,” said Bracken. “Don’t get too close.”

As they neared the pass, the witches scattered, their lanterns glimmering. Rose gave a sharp cry, and at that, the lanterns soared sidewise across the pass. Behind each lantern a thread of light spooled forth, glowing. Like spiders spinning, the witches glided back and forth and up and down. The strands wove together into a quivering web of light.

“The Veil,” breathed Bracken.

The witches were chanting now.

Rose flew above the web, scattering drops from the bottle of Wellspring water. A wind blew down the valley, stirring the threads. Then the chanting died away.

The threads began to dull and fray.

“Something’s wrong,” muttered Bracken. “Something doesn’t seem right. It doesn’t feel right.”

Scraps of Veil drifted by, gray as cobwebs. Nettle looked to the pass. The sadness she’d noticed before, the hint of a tune not remembered, still seemed to hang there. A wailing, a high-pitched crying under the stars, began. At first Nettle thought it was the wind.

“They’re crying,” said Bracken in a shocked voice. Nettle and Bracken hovered, horrified, as the others streamed past them, unseeing.

All but one.

“I thought you’d be here,” said Toadflax. She hovered near, holding her lantern high.

“It failed!” cried Bracken. “The magic failed.”

“I knew it would,” said Toadflax. She drew closer. “The Wellspring water was no good,” she hissed. “As any fool could have foreseen. The Wellsprings are ruined, ruined by humans with their stink and their noise and their trampling. It’s no good hiding here in this poor doomed little valley. Now follow me.”

“Follow you?” said Bracken faintly.

Toadflax nodded. “To my cottage. Only to my cottage. I have things to tell you. Things you need to know. Come,” she said. “Don’t be afraid. I want only the best for you.”

Nettle and Bracken stared numbly.

“And the others too!” Toadflax added quickly. “Certainly, certainly the others too! Come, it’s not far.”

Nettle looked at Bracken.

Bracken pulled her hat down low. “All right,” she said.

As they neared the cliff face, Toadflax muttered a spell and landed on the ledge. The outlines of her cottage appeared as if through a drifting fog. There was no front porch, no swing—only a rocky path to a stout wooden door. Toadflax strode forward and waited in the gloom, holding her lantern high.

Nettle and Bracken stowed their broomsticks in their pockets, then followed Toadflax inside.

“Oh!” said Bracken, stopping. Rows and rows of spell books, human-made books, and books that Nettle didn’t recognize as either sat on shelves carved deep into the rock.

“Pretty, aren’t they?” said Toadflax. “Go ahead. Take a look.”

Bracken walked along the shelves, head bent, reading every spine.

“I see you’ve noticed the Encyclopedia of Known Enchantments,” said Toadflax, running a thin finger along the volumes. “It’s too bad the others don’t have one.” She smiled. “It would have been especially useful for Rose. She’s the one who gives you your lessons, is she not? But so it goes.”

“The Encyclopedia of Known Enchantments,” said Bracken slowly. “You had one all this time and you didn’t tell anybody?”

“Selfish!” said Nettle.

“Don’t be impudent,” said Toadflax. She hung her lantern on the hook above the table. “Sit down,” she said, sinking to a seat. Her face was pale, her eyes shadowed by her hat’s wide brim. “The time has come, and then some.”

Nettle and Bracken sat on the bench across from her.

“What they won’t tell you about is the Fading,” said Toadflax.

“The Fading,” quavered Bracken. “What’s . . . the Fading?”

“The Fading is when you lose your powers,” said Toadflax.

“Your magic powers?” said Nettle, aghast.

“How could you lose your powers?” asked Bracken.

“Humans drain them away,” said Toadflax.

“That’s impossible. That could never happen!”

“You don’t think so?” said Toadflax. “It’s happened to many, many covens.” She paused. “It began in the days when we lived in the Old Country. In London.”

“In London,” echoed Bracken bleakly.

“Everyone thought it was a disease, from the stink and roar of the city,” said Toadflax. “The oldest ones succumbed first, and then the next oldest, then the next after that. The youngest ones seemed to hold out the longest.”

“And . . . they lost their powers?” Bracken seemed dazed.

“Yes,” hissed Toadflax. She leaned toward them. “It happens whenever there are too many humans near! That’s why we left the Old Country and came to this one. It’s why the Woodfolk came too. They thought they’d be safe.” She smiled wanly. “So much for that idea.”

“If you lost your powers, you couldn’t fly!” cried Nettle. She swallowed. “You couldn’t talk to animals! You’d have to lug everything around in some big, heavy bundle on your back. . . .”

“Exactly,” said Toadflax. “It is too horrible to contemplate. But that is what will happen to you when humans come to this valley. As they will, soon.” She stared at them with glittering eyes.

Bracken put her head in her hands. “This is awful. Awful.”

“Ah, but I have something that might help you,” said Toadflax. She got up and went to the cupboard. When she returned she set something down on the table.

It was round—about the size and shape of a loaf of bread—and wrapped in a soft brown cloth embroidered with oak leaves and acorns.

“A seeking stone!” gasped Bracken. “You have a seeking stone?”

Seeking stones were old and potent magic. You could gaze into one and see another witch who had one, even if she was far away.

“I thought the seeking stones were all gone!” said Bracken. “Lost . . .”

“You were wrong,” said Toadflax as she pulled back the cloth.

The stone was a smooth blue-green, veined with darker green. “It takes two stones, working together, to see anything,” Toadflax said. “Now, listen closely. . . .”

But Nettle didn’t.

She reached out, not thinking, and touched the stone’s smooth surface. Instantly, a mist rose and swirled around her.

“Fool!” shrieked Toadflax, but already her voice seemed to come from someplace far away. “Not yet! You little . . .”

Then came blackness.

chapter eight

Time and space seemed to whoosh together.

The darkness whirled.

When it stopped, Nettle was standing in a vast sunlit room. On the far side, under an archway, stood a gaggle of human children. They were staring at her, eyes goggling, mouths wide open.

“A witch! It’s a witch!” screamed one. They all began to yell and point.

Nettle stared back, frozen. If one came close she could spark it, but there were so many of them. . . .

“QUIET!” yelled a deep voice. A man and a woman appeared in the archway. “JASON. EMILY! GET BACK HERE! ALL OF YOU! GET BACK HERE RIGHT THIS MINUTE.”

“It’s a witch!” said a girl, pointing.

“She’s standing right there,” said a boy.

“Jason, that is not one bit funny,” said the man. “Line up, all of you. This field trip is over.”

“She is, she is!” said the girl. “There’s a girl right there, and she’s wearing a witch costume, and she wasn’t there a minute ago.”

“E

mily, I am surprised at you,” said the woman. “Jason, get back here.” She grabbed the boy’s arm and propelled him back in line.

Nettle held still as a rabbit, watching as the children slouched one behind the other into two long lines.

“Field trips,” sighed the man to the woman. “I don’t know what gets into them.”

The woman glared at the children. “They opened up this whole museum, the entire Atkinson House, on a Friday afternoon especially for our school, and this is how you behave?”

Moans, grumbling.

“I don’t know who is responsible for this stupid stunt,” she said, looking at Jason. “But let me just say it will be a long time before you are taken to another museum. AND I WILL BE SENDING HOME NOTES TO ALL YOUR PARENTS. Now get on the bus, all of you.”

The lines of children stumped sullenly through the archway, glancing back over their shoulders and muttering.

“Quit it,” said a girl, elbowing the boy named Jason. She was slightly taller than the others, with pale hair that fell to her shoulders. “Don’t be such a jerk.”

She looked at Nettle for a moment, her face open and curious. She smiled and gave a tiny wave.

Then she was gone.

The thumping and bumping and yelling faded.

Deep silence fell, broken only by a hollow tock, tock, tocking that seemed to come from another room. Late afternoon light slanted through the windows. A wide stairway curved gracefully upward. A thing that Nettle recognized (from a picture in the Cyclopedia) as a chandelier hung from the room’s high, ornate ceiling.

Doors made of panes of glass opened on a large garden—Nettle could see sunny flowerbeds and tree-shaded paths—enclosed on all sides by high stone walls. Nettle rattled the little brass lever on the doors, but they wouldn’t open. She turned and noticed letters written above the archway where the children had been standing: This Way Out.

She went through the archway and down a hall. It opened into another room where two big doors were flanked by tall windows. She tried the doors, but they wouldn’t open either. Outside, at the foot of a flight of marble steps, the children were filing toward something big and yellow and boxlike. Black lettering along its side said School District 561. A low, deep rumble came from within.

Backwards Moon

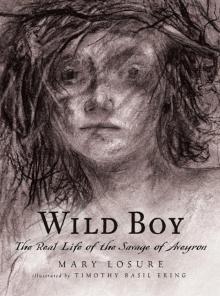

Backwards Moon Wild Boy

Wild Boy