- Home

- Mary Losure

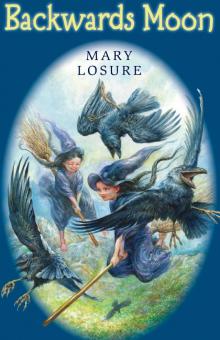

Backwards Moon Page 6

Backwards Moon Read online

Page 6

Nothing happened.

She remembered the Woodfolk cloth and pulled it out. She ran her fingers over the soft cloth, the smooth stiches, and thought about Woodfolk with a fierce stab of longing. After a long time, she wrapped the stone in the cloth and slipped it back in her pocket, but as she did her hand touched something else. She pulled it out. It was the book she’d found next to the stone in the glass case. The word Journal was embossed on the battered leather cover.

She wondered now why she’d taken some old musty- looking diary, but she opened it anyway.

Sickle Moon, read the first page. The faded handwriting was small and quick and plain.

It was wretchedly hot today, and in my human clothes I could barely breathe. I refuse to wear a corset, but there’s no avoiding the tight-waisted dress, the petticoats, the hat that must be fastened to your piled hair with a long, sharp pin. Worst of all are the boots.

I keep my own precious dress in a satchel tucked tight beneath my arm. My broomstick and hat and seeking stone are safe in the pocket.

Nettle’s eyes widened.

Broomstick?

Seeking stone?

A witch’s diary. Nettle read on.

The city is much, much bigger than I ever could have imagined. There is an incessant din of riverboats hooting, carriages rattling, hammers pounding, men shouting.

My first step must be to find a Witchfriend.

Nettle glanced at Elizabeth, still hard asleep.

It was simple to tell if a grownup human was a Witchfriend—she (or he) could see you. It was different with a human child. But Elizabeth was a Witchfriend, surely?

Nettle bent again over the book.

Quarter Moon, it said.

Yesterday in the early morning I saw a gentle old man. Something about him made me think . . . perhaps he’s a Witchfriend? Though I have been deceived before. I followed him to a bookshop.

I watched through the front window as he took off his hat and coat and hung them on a hook. He walked among the shelves, pausing sometimes to take out a volume or to run his hand along the spines.

How can you tell whether a human is a Witchfriend? It’s a brightness in the eyes, yes, but more than that. An openness. An eagerness. An abiding interest in life in all its many forms.

After a time he caught sight of me through the window and nodded in greeting.

A bell rang when I entered. He smiled, his eyes bright and sharp.

Waxing Moon

The bookseller’s name is Mr. James. Today I bought a book from him, a volume of poetry. “What an amazing thing a poem is! Like a spell, but not a spell,” I said, and watched him closely.

“Quite so,” he said pleasantly.

Half-Moon

The bookseller has a daughter named Phoebe who also works in the shop. She wears a gray dress and a black shawl and reminds me of the bird of that name. I wonder if she too might be a Witchfriend, as it often runs in families.

Yesterday they invited me to go with them on a visit. Someone wished to meet me, they said.

We rode on a streetcar and alighted by a grand stone house with towers and turrets, almost like a castle in the Old Country. A servant led us through an entranceway, then into a great, high-ceilinged room and down a passageway to a parlor where an old man—old for a human, at least—was waiting. He rose from his chair and bowed. His name, he told me, was Walter Allan Atkinson.

It was the name on the little white cards.

W. A. Atkinson.

The man who had taken the seeking stone!

Nettle felt a chill. She read on, faster.

Mr. Atkinson looked at me for the briefest moment, then the three humans exchanged a glance.

“We are Witchfriends, all,” said Phoebe.

I kept silence, for one cannot be too cautious.

“If you want to be sure of us, we can make a test,” Phoebe said gently. “We will leave you alone to put on your witch garb. We will wait in a room just down the hall. Come when you are ready. Then, if you are not invisible to us, you will know that we are telling the truth.”

I listened to their footsteps tap away down the hall.

Then I unlaced my boots and kicked them off, gladly. I took off my hat and let my braid fall free. I unbuttoned all the tiny buttons and stepped out of my human dress and bothersome petticoats. What a mountain they made on the floor!

I put on my own true dress and hat and stole down the hall. I could feel the swing of my braid and the cool, polished floors beneath my toes.

The door at the end of the hall was ajar, and through it I heard their voices. I stood for a moment, then stole silently into the room. I watched them for a minute more before Phoebe glanced up.

“Why, you look lovely,” she said.

They came toward me, smiling broadly. “I knew it,” said Mr. James to Mr. Atkinson. Mr. Atkinson bowed low. “Merry meet.”

I bowed back. “Merry meet, indeed.”

Heart’s Moon

Mr. Atkinson’s house is a Safehouse: a secret haven for witches.

For it happens that in this city on the Great River, the friends and allies of witches are so numerous that they have formed a Secret Society. They study our ways and write down all they can discover. Whether it is accurate or merely human imaginings I have no way of knowing, but Mr. Atkinson has a library of many volumes of witchlore.

The garden here is planted with enchanter’s nightshade and heartsease and many other plants that Witchfriends know provide aid and comfort to our kind. In its center grows an oak ringed by a circle of rowan trees. When Phoebe visits, we sit under the oak and talk.

The cook and the butler and the housemaids cannot see me, but the under-housemaid can. She’s become the newest member of the Secret Society.

This morning I worked up the courage to ask Mr. Atkinson whether he knew anything of a Door to another world. I explained that I had come to the city to search for it. I told him of the old stories and the Woodfolk tales of a Door that led to a world without humans. I told him then about my dream, the vision I had that the Door would be found in a city, this city. I told him I had dreamed too that it would be near a place of safety, a refuge of some kind.

He asked many questions, and he tells me he will inquire among all the Witchfriends in the Secret Society. He knows every owner of every Safehouse east of the Great River.

Both of us, now, have begun to search for clues in his library. I hardly sleep. I read by day, and at night as well, even when all the lights are dark. Sometimes when I look out the high-arched windows, I see the changing face of the moon.

Phoebe grows more anxious all the time, for she has heard of the Fading, though many in the Society dismiss it as a rumor.

Nettle hunched over the book, reading as fast as she could.

Full Moon

There is magic here, I feel it.

But how will it be revealed? The question gnaws at my very being.

Waning Moon

A troubling thing, a fearful thing: at first I thought I was only imagining it, but for several days now, my pocket has seemed oddly heavy. Then this afternoon in the garden, the sheen of my dress seemed the tiniest bit dulled. And tonight when I tried to light the fire in the library, my fingerspark seemed to sputter for an instant before it caught.

Phoebe is sure it is the Fading. She urges me to leave while I still can.

But I feel in my heart that I still have time. And the Door is so near! I feel it calling me. If I can find it, there will be no need for any of us to live hidden and cowering. We can go to a new world where we can live in freedom and happiness.

Where we will have a future.

Half-Moon

Tonight when I tried to light the fire, my fingerspark shone only the weakest blue, then guttered out. Every hour it is worse. My dull, gray dress hangs on me. My bones ache. I hear a whining sound, like a mosquito inside my head.

The broom in my hand is lifeless. It is only wood and twigs now, nothing more. I will never op

en my seeking stone again.

Soon I will become a witch who is not a witch. A shell of a being. A shadow. Or maybe I will turn to dust. Perhaps that will be my fate.

I have asked the Society to safeguard this journal, but I have cast a spell on it—my last ever—to hide its true content from human eyes. So you now, who are reading this—you must be a witch, or you would not be able to see these words, the true words, hidden from all humans.

I pray that you are young and strong and can last long enough to find the Door! It is very near. And you must find it. You must, or all of witchkind will share the fate that will soon be mine. To become a witch who is not a witch.

A shade, a shadow.

Be strong, and may Gaia speed you.

Epigaea R

The rest of the pages were blank.

“What’s wrong?” said Elizabeth. She was sitting up in bed. “You’ve been reading for the longest time, all hunched over. Nettle?”

“I found this book,” said Nettle slowly. “And it’s a witch’s diary. And this witch, she came to this city, and she stayed in that big house, that same house where I was.”

“The Atkinson House?”

“Yes. She was looking for a door. The Door to another world.”

“At the Atkinson House?”

“Yes. Or nearby.”

“And . . . you found her diary?”

“In the Atkinson House. In a glass case.”

“Wait. You stole it?”

“It’s a witch’s book! It didn’t belong to humans.”

“But you took it from a glass case? Did you break the glass?”

“I cut a hole in it.”

“Whoa,” said Elizabeth softly. “At least you didn’t get caught. But you’d better stay away from the Atkinson House, is all I can say.”

“But I can’t!” cried Nettle. “I have to find the Door!”

“But Nettle . . .” Elizabeth broke off, listening.

“Elizabeth?” said a voice. A knock sounded on the door. “Elizabeth?”

Nettle slipped from the sleeping bag and shoved it under the bed just before the door opened.

“Can I come in?” said a woman, peering into the room. “I thought I heard voices. Elizabeth, it’s ten o’clock in the morning!”

The woman standing in the doorway had Elizabeth’s pale hair and gray-blue eyes and open face. She was Elizabeth’s mother; Nettle could tell instantly. Nettle could barely breathe, she felt such longing looking at the two of them, mother and daughter, together.

“Sweetie, are you sick or something?” said Elizabeth’s mother. She stepped forward and felt Elizabeth’s forehead. “Why are you just sitting there in your pajamas?”

“I’ve been, well, thinking a lot,” said Elizabeth. “Trying to figure some things out.”

“Well, get dressed and have breakfast,” said her mother. “We thought since it’s raining we’d go to the art museum.”

“That’s okay,” said Elizabeth. “I think I’ll just read.”

“What if we went to the movies?”

“I’ve got things to do. Stuff. You know.”

Her mother sighed. “We’ll be back by afternoon. And you haven’t been to the museum in ages.”

“That’s okay, Mom.”

“Are you going over to Alice’s house?”

“Alice is gone on a trip. Remember?”

“Well, all right,” said her mother. “There’s oatmeal. I made oatmeal. Leave a note if you go anywhere, and this time be home for dinner. Got that?”

“Right,” said Elizabeth.

The door closed.

They watched from Elizabeth’s parents’ bedroom window as the car rolled down the street and away.

“A door?” asked Elizabeth. “You really think there’s a door to another world?”

“All I know is what I read in the diary. And it said if you are reading this, it’s up to you to find the Door to another world.”

Elizabeth frowned. “Now what are you going to do?”

“Go to the Atkinson House. Look for the Door.”

“You can’t go! Not today! Remember? Jason and those other kids will be looking for you.”

“I’ll go tonight then,” said Nettle.

Elizabeth nodded slowly. “Tonight.” She brightened. “But anyway, now we have today at least. Come on downstairs.”

It was funny, really, how that day with Elizabeth stuck out in Nettle’s mind forever after.

They walked around her house and looked at everything. They went to the kitchen, which was full of strange inventions: a humming box, and things that dinged, and a stove that made flames with a click and a whoosh. They sat at the kitchen table and ate strange human food. But most of all, they talked.

Elizabeth told Nettle about school, and the kids at school, and Nettle had lots and lots of questions. “Don’t witches go to school?” Elizabeth asked finally.

“We have lessons with Rose,” said Nettle.

“Magic lessons?”

“Yes.”

Elizabeth sighed. “I am so envious, I cannot tell you how envious I am.”

They talked about their families: Elizabeth’s mother and father and aunts and uncles and cousins. . . .

Then Nettle told Elizabeth about Bracken and how the two of them were cousins and lived with Great-Aunt Iris. “The others in the village, Rose and everyone—well, everyone except this one witch—they all live close. In this little circle of cottages. We can all see each other’s front porches.”

Elizabeth hesitated. “What about your parents?” she asked quietly.

Nettle looked away. “Our mothers are gone, and our fathers too. They disappeared. And our grandmother died of sorrow, and Aunt Iris took us to live with her. I was only a baby, and Bracken was really little.”

“That’s awful,” said Elizabeth. She bit her lip, frowning. “But your parents. . . . Nettle? What happened to them?”

“No one in the village would ever say. But now . . . I think now they went into the other world.”

“You really think so?”

Nettle nodded slowly. “Yes.”

Elizabeth frowned. “So, you think they just left you and your cousin behind?”

“No! I think something must have happened. Because they never would. Not on purpose.”

A silence, then Nettle said, “I think if I find the Door, I might be able to see them again.”

“Oh,” said Elizabeth softly.

“Maybe there are clues in the diary,” Elizabeth said after a while.

Nettle pulled out the diary and handed it to her.

“A Natural History of Witches,” Elizabeth read aloud. “A Field Guide to the Habits, Customs, and Culture of the Various and Sundry Folk Known . . .” She looked up. “This isn’t a diary.”

“Huh,” said Nettle “There must be different words when humans read it.”

Elizabeth turned the page. “There might be clues here!” She flipped forward, scanning the pages.

“Read it out loud,” said Nettle.

It was all about witches. “Wow,” Elizabeth kept saying, looking up from the pages.

But nothing seemed to lead to the Door.

Then Nettle read the diary aloud to Elizabeth, with all its hidden-from-humans words.

But still, nothing seemed like a clue to the Door, or maybe everything was and the key was to sort it all out, but all it did was make Nettle’s head hurt.

They talked then about whether Elizabeth should come too, when Nettle went to the Safehouse that night. But in the end, they decided Elizabeth could be seen, and that would put Nettle in danger. So however much Elizabeth wanted to ride a broomstick, she wouldn’t. They decided Nettle should wait until late, when for sure there would be no one inside the Atkinson House.

They were in the kitchen eating something called peanut butter sandwiches when Elizabeth’s parents came home—Elizabeth heard the car in the driveway. Nettle ran upstairs to Elizabeth’s room.

Later Eliz

abeth came up and they read her books—she had wonderful ones—until suppertime. After supper Elizabeth brought Nettle some smuggled food and they read some more, but it was hard to concentrate on anything. And then at last it was late; Elizabeth’s mother came to say good-night and then went away again.

“Good luck,” said Elizabeth gravely as Nettle pulled out her broomstick. “You know the way, right?”

“To the Atkinson House? Yes,” said Nettle.

“I mean here too. 721 Elm Street. In case you need to come back.”

Nettle nodded.

“Good-bye then,” said Elizabeth sadly. She opened the window wide.

Nettle bowed. “Fare-thee-well and merry be.” She paused awkwardly, then suddenly pulled the diary—A Natural History of Witches—from her pocket and handed it to Elizabeth. “Here,” she said. “You can keep it. And thank you for helping me.”

chapter fourteen

The rain fell steadily, sloshing in rivers down the front window of the pickup truck.

A sort of blade moved back and forth across the window, swishing off the water with a steady thwak, thwak, thwak.

Bracken glanced at the farmer, but he didn’t seem tired.

“Aren’t you going to need to sleep sometime?” she asked at last.

Ben shrugged. “It’s kind of strange. I think it’s the spell, but I don’t feel tired at all.”

In the middle of the morning they stopped at a place called Gordie’s Econo-Mart. The farmer came back with a large brown bag, a jug of water, and a little dish. “For the coon,” he said. “So he can wash his food before he eats it. They do that, you know. I bought him some sweet corn too.”

He set the things in back, then steered the truck along a dirt road past a sign that said WAYSIDE REST. It turned out to be a clump of trees and some rickety wooden tables, each with a roof over the top. Raindrops splattered on the roofs and blew in on the tables.

“We’ll reach the city by tonight for sure,” said Ben after they had eaten. “It will be a miracle if we find the Safehouse, though. I mean, I’m happy to try. But it really sounds like a long shot to me.” He shook his head. “A very long shot.”

Backwards Moon

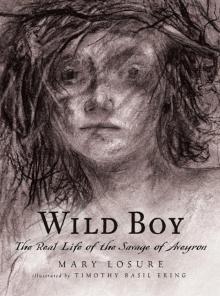

Backwards Moon Wild Boy

Wild Boy